Question: white Burgundy – is it investable?

Answer: absolument!

by Juliette Martin

2021-08-06

The problems with white Burgundy in the past have been well documented; namely premature oxidisation, or premox for short. In a former job spec, managing FCA grade wine investment funds, the problems were enough for us to have one simple discipline when it came to white Burgundy – do not invest. Although I have seen thousands of pounds worth of Grand Crus literally poured down the sink from vintages past, these problems are behind us now and there is more belief in this area than possibly ever before. The grandest Crus stand head and shoulders above their peers in much the same way as their red counterparts do, and they always will. After all, they have been growing grapes in them there hills since 150 B.C. according to Neal Martin’s excellent recent piece for Vinous Media, so they know a thing or two about the land and how to achieve the best results.

Again, like the reds, the vineyard areas are small, so production levels are low. There are less than half the number of white Grand Crus compared to red however, and the famed village of Meursault is not even deemed worthy of having a single one! There are two that do both, namely Corton and Musigny. The very top producers have been sold by allocation only for some time now, but are still behind the reds in that regard, and on average price too. Buyers should not only look at Grand Crus as there are many superb Premier Crus too that can deliver – even some in lowly Meursault! Also, it is not necessary just to stick to names with ‘Montrachet’ in them, there are some viable options from other villages and Chablis of course. The Côtes of Maconnais and Chalonnaise are not made of quite enough stuffing to qualify for ‘investment grade’ but there’s no doubting the quality of these wines continues to rise.

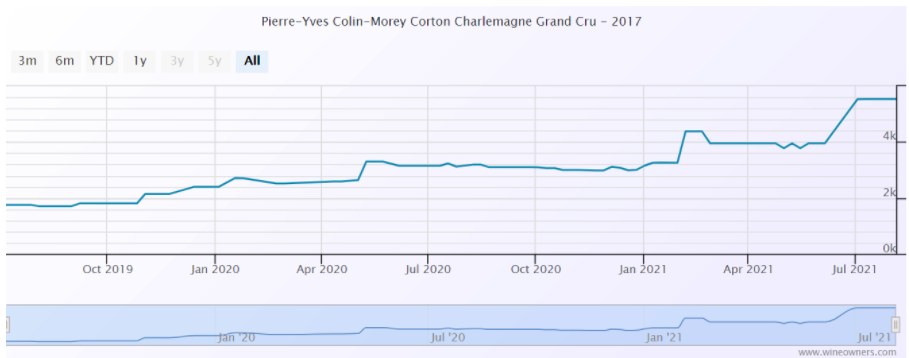

White Burgundies tend to disappear off the market after a few years of age as global demand far outstrips supply. This makes valuations and therefore performance numbers hard to measure accurately so you’ll just have to believe me that they really can perform. Here’s one example of a young wine since release (c.50% annualised ROI!):

I happen to think that this wine has not stopped motoring yet, and there are only but a couple of cases (six packs) currently on the market. Why do I say this? Because prices for white Burgundies are still a fraction of their equivalent red counterparts, there is less of it, and there is vast burgeoning demand, and it is global. There is also the threat that global warming may mean there’s even less of this stuff to go around in the future, and perhaps not as well balanced, classical and chiselled as we are used to.

As a rough guide, village wines should probably be drunk between three and ten years of their life, Premier Crus five to fifteen and Grand Crus ten years plus, they can last for decades. My advice would be, if you are buying into this rationale, is to invest primarily in good producers, most Grand Crus (if they haven’t already tripled!), and then in highly rated premier crus (particularly from the ’14 and ’17 vintages). Obviously, the vineyards are important too and the ‘jewel in the crown’ sites of producers can often produce an extra bit of uplift.

Some of the names to look out for, amongst others:

- Boillot, Henri

- Bonneau du Martray

- Coche Dury (‘silly money’!)

- Comtes Lafon

-

Dauvissat

DRC (‘silly money’!)

-

Leflaive

- Moreau, Bernard

- Pierre-Yves Colin-Morey

-

Ramonet

- Raveneau

-

Roulot

Posted in:

Tags: